As the Q1 GDP numbers came in for the Baltics I concluded that it was very likely that the region had entered a recession. In light of the proverbial definition of a recession as a consecutive quarter contraction it seems clear the Lithuania managed to smartly skirt the recession in H01 2008. As far as I can see at this point and from Eurostat's data Estonia was the only one of the three Baltic economies that contracted in Q1 2008 (-0.5% and 0.1% for Latvia).

However and as ever before, the Baltics is increasingly getting stuck in stagflation and one of a particular sinister kind. In the case of the Baltics they may already be seeing the beginnings of a hard landing, whereas others continue to build up steam making it almost inevitable that they too will erupt at some point. insert graphs below ...

As can be observed, Lithuania just managed to avoid a contraction in Q1 and rebounded nicely in Q2. Yet, in light of the run-up to these numbers and the fact that Lithuania, on a y-o-y basis, grew at its lowest rate since 2004, I have little problem in maintaining my view that this is a hard landing. As for the break up of Lithuania's position it is a bit difficult to tell since the components do not feature seasonally adjusted figures. However, it seems that especially companies paired their investments going in to 2008 while consumers are still going strong. All three forward looking indicators in the form of confidence measures show that the expected trajectory of overall momentum is firmly down.

The other graphs reveal with some clarity I think that the Baltics may now be entering a whole new different growth dynamic with inflation and wages continuing their upward drift at one and the same time as growth is faltering. In this way, it is hardly about the potential recession and slowdown itself but about the economy, and growth rate, which will emerge. This point is similar to one I made recently in the context of the Eurozone and I do think it is important to realize the hole some of the CEE economies are about to dig themselves out of. In fact, depending on the reversion into wage and asset price deflation I would say that this slowdown marks a significant structural break in these economies' growth path.

Consequently, there is simply no way in which these economies can muster the inflows they have been receiving and actually many face a decisive need to turn the boat around and become export dependent. The key link will be the extent to which we, at some point, will observe to wage deflation to reign in the external position absent a currency to devalue. With a fixed exchange rate to the Euro and an extremely wide external position the only way a correction can come is then through severe wage and by consequence price/asset deflation. The alternative would of course be to the abandon the pegs but that would then open up Pandora’s box as the currency most likely would plummet to reflect the external balance leaving Baltic consumers with Euro denominated loans and cash flows in domestic currency (get detailed argument and analysis here, here and here).

Another crucial link here would be Scandinavian banks who are effectively supplying these Euro denominated loans and thus how they, effectively, are financing the deficits as they currently stand. We have thus on several occasions been hearing faint but rising voices about how, in particular, Swedish banks are exposed to the Baltic slowdown. In a recent detailed analysis John Hempton from Bronte Capital serves up some nice points on the whole situation. What is particularly interesting is that he takes the time to scrutinize the books of Swedbank who is operating its subsidiary Hansabank which is, by far, the biggest foreign bank in the Baltics.

One of the important points to latch on to was the one conveyed in my last look at the macroeconomic balance sheet of the Baltic economies. In this analysis I showed that while loans in local currency are now falling on a stock basis (i.e. the amount of loans being paid out or written off outnumber the number of new loans taken out) it is still growing in Euro denomination effectively keeping overall stock of loans in the positive, even if the trend is inexorably down. Once I have Q2 data for all the Baltic economies I will post briefly on the development.

Yet, if you dig into the Q2 accounts of Swedbank (who are operating under the branded name Hansabank in the Baltics) you will see that they are still churning out positive growth rates in lending in Q1 and Q2. Over the course of H01 2008 Swedbank consequently expanded their lending operations with 7% in the Baltics and over the entire year, this number stands at 21%. If we compare this to the growth in deposits in the Baltics the H01 figure is 1% whereas it is 11% over the year. As such, levering of the balance sheet continued in H01 2008. In short, lending growth is still positive and the leverage multiple measured as the value of lending over deposits is growing.

I don't think it is entirely outlandish to draw a line between my initial results derived from macroeconomic data to these results from one of the biggest players on the Baltic finance market. Personally, I don't see how the growth rate can continue to stay in positive territory and this is especially the case since net interest income is now beginning to decline, if ever so slowly.

In the context of cooking, as it were, the books of Swedbank Hempton makes another interesting observation in his piece.

Now, Mr. Hempton certainly does not mince his words and even though he may come off as wing nutty the point being made is actually quite simple. What he effectively is doing then is to move the translation risk perspective to the middle ground between the obvious crunch that would ensue as consumers defaulted on their loans to the predicament which would arise in the context of Swedbank's books.

What it means in macroeconomic terms is that if the translation risk issue blows, which it potentially will in the context of wage deflation (i.e. this would force down the pegs), Hansabank would effectively be screwed. Sorry for my harsh tone, but I I cannot see how they could shore up their balance sheet unless the ECB moved in with a kind of 1:1 guarantee which let the Baltics de-facto adopt the Euro with one swoop. Now, if Hansabank goes, and this seems to be Hempton's argument, so could Swedbank and by derivative the inflows used to fund to external deficit to the Baltics. And then we are into a royal mess.

Also, one could easily imagine a rather advanced game of Old Maid since if Hansabank et al. suddenly move seriously into the ropes, de-pegging would almost certainly mean that a significant write-off of Euro denominated loans would ensue in which case the Baltics may neatly shift some of the heat on to Swedbank who, almost certainly, will be running to the Riksbank and then perhaps on to the ECB.

Ultimately, I think the Baltics will fight long and hard against devaluation and much will depend on the severity of the correction. It may end up a perfect storm for them, but I want to stress that this would require the ECB to step in with some kind of de-facto, behind the curtains, guarantee to the currency board. That is to say, the ECB or the Riksbank would need to foresee the chain of events above (or a derivative thereof) and nip it, preemptively, in the b*t so to speak.

Quit With the Dooming and Glooming Already?

Uff that was some outlook was it not? I should immediately point out that much of this represent musings at this point and should not be taken literally. However, I have pointed out the shaky links between Scandinavian banks and the Baltics more than once, so it should not come as a big surprise.

If we move up the perspective to macroeconomic the points above relate to more general point concerning the Baltics and the manner in which the current imbalances potentially will be corrected. This consequently lays out a path well trodden here at Alpha.Sources. As the rest of the CEE countries, the Baltic economies have quite simply been converging too fast given their underlying capacity (read: demographic) constraints. In fact, given the loop sided nature of almost all CEE economies after two decades worth of lowest low fertility the whole convergence hypothesis was always going to hit shallow waters. As such, and coupled, in the past 5-6 years, with significant outward migration, these economies have quite simply been administering a growth strategy wholly incompatible with their underlying fundamentals.

This obviously does not mean that Eastern Europe will sink into the ground but it does mean that a correction is due, both in terms of expectations and the trajectory of economic fundamentals. Note in passing here especially how this will affect Germany's ability to leverage its export muscle towards its Eastern borders. In a more broad policy oriented context I have also been amazed, even if I can understand it, with the push to de-peg from the Euro and subsequently raise interest rates. Sure enough, when you have imported inflation you want a strong currency but in administering this kind of policy you are also assuming that the implied process of nominal convergence can be speeded up; almost as if the CEE economies could attain nominal convergence with EU15 in one clean and bold sweep.

Conclusively, my guess is that while Q2 data will tell give us important forward looking indicators Q3 and Q4 may be where the real action is. As per reference to my points above I am watching FX markets in particular and, in the case of the Baltics, the link with Scandinavian banks and the potential ways in which these economies can correct.

Here at Alpha.Sources your devoted author is struck by hardship at school as he labours (with his mates) to finish a paper by next week on the juicy topic of determining the factors which guide prices and returns on subordinated debt in the European leveraged finance market. However, having upated his Eastern European (Baltic) excel sheets recently he feels compelled to move in with some observations on the evolution of bank lending in the Baltics and why investors should be a little bit weary of buying into the main trend at the moment where high inflation rates are leading markets to price in revaluation across the board in an Eastern European and Russian context.

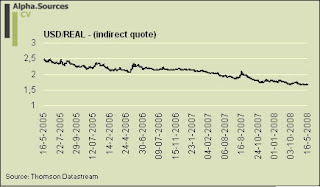

The immediate context of overheating economies in Eastern Europe and the subsequent expectation of revaluation recently was epitomized in the flurry about the Hryvnia in Ukraine but also Hungary was 'forced' recently to scrap the Forint's trading band. In the context of this emerging market discourse and not least the growing pressure on Russia to let traders punt the Ruble (don't worry Macro Man, your day will come) I recently asked the simple question of whether in fact the process of nominal appreciation would a be a natural consequence of making the exchange rate more flexible. The point is simply that while nominal appreciation may indeed quell imported inflation it is also likely to add to an already raging inflation bonfire in Eastern Europe driven by excess domestic demand over capacity which is fuelling unsustainable wage growths, large external deficits and by consequence large inflation rates. As a response to my piece RGE's inhouse analyst on Eastern Europe Mary Stokes also moved in with an excellent writ in which she basically asked whether pegging currency regimes were to blame for the travails of many Eastern European countries?

As Mary eloquently sums up many Eastern European countries are now in a bind as real economic activity is plummeting at the same time as inflation remains. This is especially true for the Euro peggers (such as e.g. the Baltics and Bulgaria) where now seems no meaningful adjustment mechanism except domestic deflation and should the pegs be abandoned (I think ultimately they will) where will this take these countries?

In this specific note I want to focus on the Baltics whom I have had under the spotlight several times at this space. Recently, we got evidence that all three Baltic countries had slowed sharply going into Q1 2008 essentially dropping into a recession. Traditionally, my analysis on the Baltics have been focused a lot on the financing of the three countries' external balance as well as the the currency composition of the credit inflows which make up a decisive part of the financing. Specifically I have been indulging on my Lithuania fetish in an attempt to go deep in the context of one country in order to be able to make extrapolations on similar countries. Most recently I discussed the drivers and availability of foreign credit in Lithuania (Euro denominated loans). In the following I present a similar analysis for all three Baltic countries and the results should not be taken lightly I think.

The stylised facts are as follows:

As we observe the stock of household (and I would imagine also corporate) loans in the Baltics are overwhelmingly in Euros. This is hardly news and at this point is well incorporate into market discourse in the Baltics. Yet, if we look at the evolution we can see since the credit turmoil began (more or less) economic agents in the Baltics have been shifting their liabilities into Euros. This effect seems especially pronounced in Lithuania where a hump in LTL loans is now giving way to an increase in Euro denominated loans. The immediate underlying driving force cannot be read from the graphs above in the sense that this may be a sign of loan rollover/conversions as well as a sign that the flows are simply changing.

As we observe the stock of household (and I would imagine also corporate) loans in the Baltics are overwhelmingly in Euros. This is hardly news and at this point is well incorporate into market discourse in the Baltics. Yet, if we look at the evolution we can see since the credit turmoil began (more or less) economic agents in the Baltics have been shifting their liabilities into Euros. This effect seems especially pronounced in Lithuania where a hump in LTL loans is now giving way to an increase in Euro denominated loans. The immediate underlying driving force cannot be read from the graphs above in the sense that this may be a sign of loan rollover/conversions as well as a sign that the flows are simply changing.

I think that these three graphs tell a tremendously important story. As we can see the total stock loans denominated in domestic currency are now in decline across the Baltics which reflects the general economic slowdown and tightening of credit conditions. However, as I also showed recently in the context of Lithuania the negative interest rate spread in favor of Euro denominated loans seem to favor Euro denominated loans. This, perhaps coupled with expectations of revaluation, is helping to keep the change in loans in a positive reading solely on the back of an increase in Euro denominated loans. I think this is important. It is consequently difficult to see exactly what is going on. General economic conditions prescribe that we should observe a downward trend in loan taking. Such tendencies are clearly observable in the graphs above. The lingering trend in the context of Euro denominated loans can be due to two things in my opinion. A favorable interest rate spread over domestic currency loans as well as an expectation that the domestic currencies should increase in purchasing power on the back of strong inflation pressures and thus perhaps an expectation that Euro membership is not as far away as it may look.

I think that these three graphs tell a tremendously important story. As we can see the total stock loans denominated in domestic currency are now in decline across the Baltics which reflects the general economic slowdown and tightening of credit conditions. However, as I also showed recently in the context of Lithuania the negative interest rate spread in favor of Euro denominated loans seem to favor Euro denominated loans. This, perhaps coupled with expectations of revaluation, is helping to keep the change in loans in a positive reading solely on the back of an increase in Euro denominated loans. I think this is important. It is consequently difficult to see exactly what is going on. General economic conditions prescribe that we should observe a downward trend in loan taking. Such tendencies are clearly observable in the graphs above. The lingering trend in the context of Euro denominated loans can be due to two things in my opinion. A favorable interest rate spread over domestic currency loans as well as an expectation that the domestic currencies should increase in purchasing power on the back of strong inflation pressures and thus perhaps an expectation that Euro membership is not as far away as it may look.

In many ways, as Edward also hints in a recent article the oil discoveries mentioned above represent a good initial image of

Thus assured of Brazil's importance we should take a few steps back and have a look at the historical economic performance of Brazil, how it got to where it is today and where it is likely to go in the future?

It does not take much of a macroeconomist to see how the stories above tell a story of rapid economic development. Obviously, it is difficult to make solid conclusions solely on the basis of growth figures but as can readily be observed

This role is of course shared by the other usual suspects who make up the notorious BRIC group so famously coined by Goldman Sachs. I would not want to take anything away from GS here but simply note that the BRIC narrative is not exactly fitting for what is happening in the global economy. It is indeed true that the four economies are amongst the fastest growing economies of the world but they are very difficult in terms of structural setup which tends to blur the analysis. Specifically, I would distinguish between

Brazil's rise not only in terms of GDP at constant prices but also in PPP terms cuts right across the whole debate on de-coupling which at times has developed into a rather badly played football match between the US and Europe. In this way, I never really was a fan of the original idea of de-coupling whereby the Eurozone ascended to take over from the

Too Much of a Good Thing?

Alas, this global process of re-coupling is not a linear and steady process and it is getting clouded by the Bretton Woods II edifice in which Asian economies alongside petro exporters maintain a fixed exchange rate policy to the US accumulating vast reserves in the process.

This note shall not dwell extensively by the pace of the demographic transition in  As can be observed there is some uncertainty as regards to the pace of fertility decline going into the 21st century. What can see however is that

As can be observed there is some uncertainty as regards to the pace of fertility decline going into the 21st century. What can see however is that

As I will sketch out below I believe that

Letting the Capital Flow?

Consequently as we home in on the issues of global imbalances, Bretton Woods II, excess liquidity

Keep Drilling; when an Ugly Duckling turns into a Swan?

If the UIP does not hold we can attempt a carry trade which essentially exploits the interest rate differential between the two countries. Note that in the example below our domestic investor (Ms Watanabe) lose money as the funding currency (the Yen) appreciates.

Assume:

USD/JPY: 115 (indirect quote) - after one month

Monthly JPY rate: 0,012%

We progress in the following steps (amount invested 100 USD)

1. Borrow amount equal to 100 USD (i.e. 12000 yen) in domestic money market and convert spot to invest in the US (i.e. invest 100 USD in US money market)

i.e. [(11596-12014,4)/11596]*100 = -3,61%.